Doesn’t it seem like everyone is more stressed out these days? Stress is everywhere in our lives, and poor diet and lifestyle choices compound the consequences of it on our overall health. Although stress is ubiquitous, there are ways to guide patients in managing it, including its impacts on gut health.

Gut Reaction: How Stress Impacts GI Health

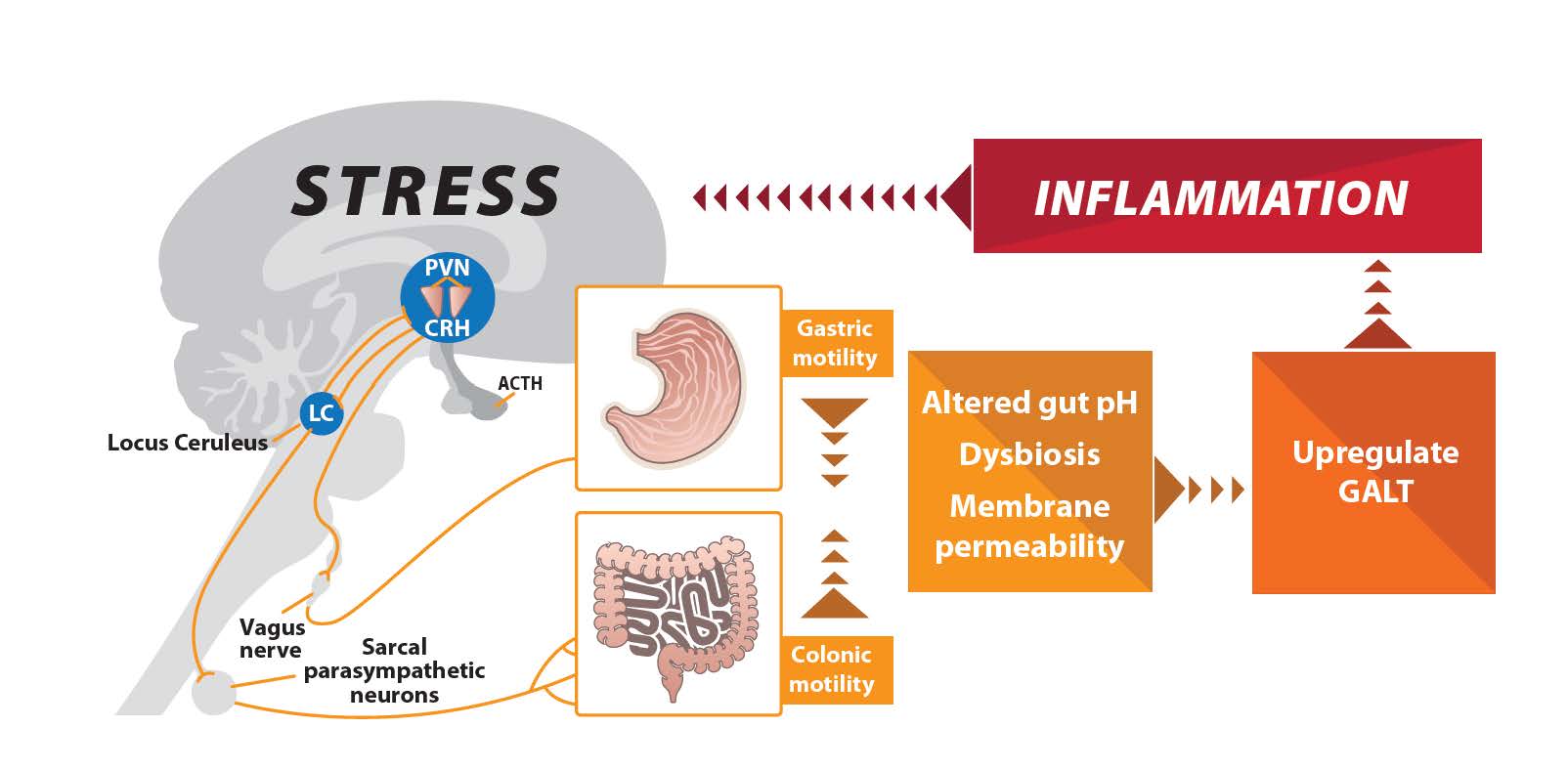

Our bodies have their own stress management system called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), which is central to managing gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. Prolonged exposure to stress—along with irregular or unhealthy dietary, sleep and exercise habits—can alter gut-brain interactions via the HPA axis. This directly affects GI function, potentially leading to a broad array of gut issues.1

As you may have seen in your patients, stress affects the following areas of gut physiology:

- Motility: Increases GI motility and defecation while also reducing gastric emptying

- Secretions: Changes GI secretions, including HCl, enzymes and bile

- Microbiome: Changes the composition, diversity and number of gut microorganisms, which alters the commensal microbiome

- Permeability: Increases intestinal permeability by affecting the tight junctions

These stress-induced bowel changes are mediated by inflammatory imbalances, causing changes within the HPA axis. They also can result in altered gut pH and dysbiosis, which leaves patients vulnerable to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), pathogenic organisms, mucosal barrier disruptions and upregulation of the immune system.2

Making the HPA Axis Connection

Have you ever wondered why your patients with prolonged inflammatory imbalances seem to have endless gut issues? The HPA axis model may explain a large part of the problem.

Pituitary Gland

Within the HPA axis, the brain and pituitary gland release hormones in response to stress that can directly affect GI function, such as motility. Specifically, the hypothalamus peptide, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), is stimulated by stress and affects GI function through brain and peripheral CRF receptors.

Thyroid

When it comes to gut motility issues, we also need to consider the thyroid. Changes in thyroid function affect our gut, and the GI manifestations of hypothyroidism are generally due to reduced motility. Increased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and decreased circulating levels of T3 and T4 are associated with slow digestive processes and decreased bowel transit time. Thyroid issues can also wreak havoc on the gut microbiome.3 For example, changes in gut motility are associated with SIBO.

Vagus Nerve

Outside of hormonal mechanisms, the vagus nerve is another, more direct line of communication between the brain and the gut. Vagus nerve dysfunction caused by prolonged stress leads to slowed peristalsis, or prolonged transit time, leaving the patient vulnerable to changes in the microbiota and HPA axis deficiencies.4 Also, there is an association between vagal nerve dysfunction and traumatic brain injury (TBI). For example, it would be wise to think “vagus” if a patient presents with SIBO symptoms and has a history of TBI.

Breaking the Stress Cycle

The cyclical relationship between stress and GI dysfunction needs to be addressed in both systems simultaneously to provide comprehensive support for the complete restorative process in your patients.

Alongside key GI nutritional supplementation, there are several ways you may improve the gut-brain connection, including the following:

- Making time for relaxation: Scheduling downtime allows the body to regenerate and helps improve overall well-being.

- Mindful eating habits: Eating slowly, eating with other people and regular dietary habits can have a positive impact (e.g., “rest and digest”).

- Meditation and deep breathing: These centering practices are beneficial traditional approaches to relaxation and stress reduction.

- Vagal nerve stimulation techniques: Gargling, singing, laughing, and taking slow, deep breaths are examples of vagal nerve stimulation techniques. These can be used a few times a day for several months to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Clinical strategies in your office: Heart rate variability measurements, cognitive behavioral therapy and biofeedback are important clinical strategies used to help manage patient stress.

In Closing

As a practitioner who employs a functional medicine lens, you understand that gut health is more multidimensional than meets the eye. Considering the HPA axis will bring a broader perspective to your diagnostic picture, helping you uncover the root causes of dysfunction beyond the gut. No matter what causes your patients’ day-to-day stress, utilizing proven stress management techniques in combination with targeted natural therapies can capitalize on the distinct relationship between stress and the gut to bolster overall GI health moving forward.

Joseph Ornelas, PhD, DC is the Pillars of GI Health Brand Manager at Lifestyle Matrix Resource Center. He holds a PhD from University of Illinois with concentration in Health Economics, an MA degree in Public Policy from the Harris School at the University of Chicago, an MS degree in Health Systems Management from Rush University, and a DC degree from National University of Health Sciences. As a licensed provider and health economist, Dr. Ornelas has published numerous evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, helping to improve quality standards of care and provide value for health care practitioners across several specialty areas.

References

- Appleton J. The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018 Aug;17(4):28-32. PMID: 31043907; PMCID: PMC6469458.

- Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol Stress. 2017 Mar 19;7:124-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001. PMID: 29276734; PMCID: PMC5736941.

- Knezevic J, Starchl C, Tmava Berisha A, Amrein K. Thyroid-Gut-Axis: How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function? Nutrients. 2020 Jun 12;12(6):1769. doi: 10.3390/nu12061769. PMID: 32545596; PMCID: PMC7353203.

- Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G, Hasler G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 13;9:44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044. PMID: 29593576; PMCID: PMC5859128.