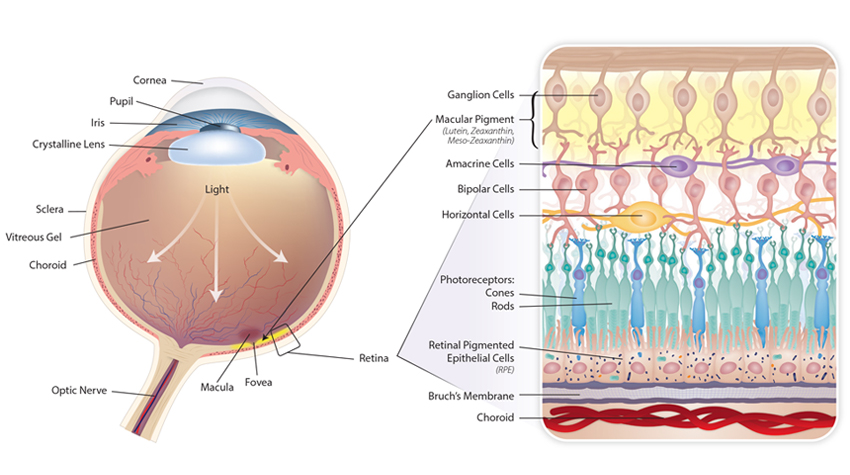

Figure 1: Basic Anatomy of the Eye and Retina. The retina is the light sensitive tissue lining the back of the eye, responsible for converting visual light into electrical impulses which exit the eye via the optic nerve and travel to the visual cortex of the brain. The macula is a pigmented area responsible for high visual acuity, it is also known as the macula lutea (“yellow spot”) due to the concentration of macular pigments at this location. The fovea is the center of the macula; here the inner layers of the retina are displaced for greater visual acuity – as indicated by the dip in the diagram. The inset image depicts the highly ordered cell layers of the retina showing each of the cells. See text for details about each cell.

Since doing my initial research for The Original Prescription, in which I discuss the benefits of lifestyle synergy, I keep running into more and more data confirming the overall health benefit of multiple “signals” coming from a variety of lifestyle decisions. Therefore, in our recent project investigating the lifestyle and nutrient strategies for the prevention and treatment of macular degeneration (AMD), it was not at all surprising to find out one of the most vulnerable tissues in the body, the retina, can be protected by a synergy of good lifestyle decisions. However, before delving into the specifics of these lifestyle-related studies, let me first discuss what makes the retina such a good measure of overall health (or chronic disease) in the first place.

There are three features of the retina that make it more vulnerable to aging and degeneration through oxidative stress: (1) constant exposure to visible light, (2) high tissue oxygen consumption (given that the retina is the most metabolically active tissue in the body per unit weight), and (3) the high concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the photoreceptor outer segments. As ultraviolet light passes through the retina, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated. The conversion of light energy into a nerve impulse by the photoreceptors generates even more free radicals. These highly reactive molecules will quickly oxidize adjacent molecules (lipids, proteins, etc.) within the cell if they are not quenched by one of several antioxidants. Therefore, since the microenvironment at the retina is primed for oxidative damage through ROS formation, it is essential that the retina has an adequate reserve of antioxidant activity to terminate oxidative reactions before they can begin damaging retinal structures. However, as with most other chronic metabolic diseases, aging, genetic predisposition and/or unhealthy lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, poor diet, etc.) can deplete the antioxidant reserves of the retina, leading to progressive oxidative damage to the sensitive molecules and tissues.

Beyond this, it is now clear that the complex progression of cellular processes leading to macular degeneration involves oxidative damage, immune system dysregulation, sluggish cell enzyme activities and chronic inflammation. In other words, while retinal degeneration manifests differently than many other chronic diseases (i.e., atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s, osteoarthritis, chronic kidney disease, etc.), its progression is likely to be coincident with chronic disease progression in these other vulnerable tissues. Noting the retina’s unique vulnerability to oxidative and metabolic damage and the fact that changes in retinal health can be easily (and non-invasively) measured, many researchers believe AMD progression can act as a “canary in the coal mine” for overall chronic disease burden.

Now back to how lifestyle medicine can be our best ally in the prevention and treatment of AMD. One of the best examples comes from an ancillary study of the larger Women’s Health Initiative, where researchers examined the retinas of 1,313 female participants and compared how certain lifestyle patterns affected their incidences of macular degeneration. In this case, they examined their diet, physical activity and smoking habits. They used two measures of dietary intake: a modified healthy eating index (mHEI) and also an alternative Mediterranean diet score (aMed). They found that women who consumed the best diet (highest quintile of the mHEI) had 46% lower risk of AMD than women with the lowest mHEI score (The risk was even lower [68%] in the best aMED scores, but only 58 of the 1,313 women achieved this score, and the researchers suggested that American women are unlikely to change their diets this much). Beyond this, they showed a 54% reduced risk of AMD in women who exercised the most (compared to those who were essentially sedentary) and a 45% higher risk for women with the highest number of cigarette “pack-years” (compared to those who never smoked).

The researchers then created a six-point healthy lifestyle score that weighted each of the three lifestyle measures and their respective impact to see how the combined “score” would impact AMD risk. The women with the highest combined beneficial lifestyle (scoring six on the six-point scale) had a 79% lower risk of macular degeneration compared to women scoring between zero and two on the healthy lifestyle score (P <0.001).

This just confirms what we have seen when we multiply lifestyle signals, similar to the 92% reduction in sudden cardiac death in the healthiest female subjects (part of the Nurse’s Health Study) when multiple lifestyle habits were evaluated (diet, BMI, physical activity and smoking). I would bet that if they measured a few more traits, like perceived stress and sleep time, they might have even seen a greater benefit of risk reduction.

This is exciting news. Making the right choices over a long time has a profound impact of preserving tissue function, building metabolic reserve and slowing the progressive process of cell degeneration that can lead to chronic disease. Our additional research, which we outline in our latest Standard Monograph, shows that some of these same signals (dietary changes, specific nutrients like lutein, weight reduction, smoking cessation) can, when intensified, act as therapeutic interventions for those who may not have practiced a prudent lifestyle in the past. In fact, since there are no approved therapies for the most common form of AMD (dry), lifestyle-related prevention and intervention are currently the only proven strategies of success.

1Mares JA, Voland RP, Sondel SA et al. Healthy lifestyles related to subsequent prevalence of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Apr;129(4):470-80

2Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rexrode KM, et al. Adherence to a low-risk, healthy lifestyle and risk of sudden cardiac death among women. JAMA. 2011 Jul 6;306(1):62-9.

| About Thomas G. Guilliams Ph.D. Thomas G. Guilliams Ph.D. earned his doctorate from the Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee) where he studied molecular immunology in the Microbiology Department. Since 1996, he has spent his time studying the mechanisms and actions of natural-based therapies, and is an expert in the therapeutic uses of nutritional supplements. As the Vice President of Scientific Affairs for Ortho Molecular Products, he has developed a wide array of products and programs which allow clinicians to use nutritional supplements and lifestyle interventions as safe, evidence-based and effective tools for a variety of patients. Tom teaches at the University of Wisconsin-School of Pharmacy, where he holds an appointment as a Clinical Instructor; at the University of Minnesota School of Pharmacy and is a faculty member of the Fellowship in Anti-aging Regenerative and Functional Medicine. He lives outside of Stevens Point, Wisconsin with his wife and children. | |

The Standard: Preventing and Treating Age Related Macular Degeneration

This new monograph explores the evidence related to specific dietary, lifestyle and nutrient supplementation therapies tested for the prevention and treatment of AMD. “Preventing and Treating Age-Related Macular Degeneration” is one of the most concise, up-to-date and relevant pieces available on this topic.