How many patients walk through your door with a chronic disease diagnosis? If you answered, “almost all of them,” then you see mitochondrial dysfunction daily. In cell physiology, you learned that mitochondria are the powerhouses of cells; they are responsible for creating cellular energy, known as ATP. However, we often forget how mitochondria are negatively impacted by HPA axis and metabolic stressors, certain medications, and poor lifestyle habits.

When we consider that some of the most mitochondria-dense tissues in the body are the heart, liver and brain, we can see how many diseases of those tissues need mitochondrial support. Additionally, mitochondria have been implicated as key regulators of both innate and adaptive immune function through metabolic and cell-signaling mechanisms. Therefore, knowing mitochondrial dysfunction plays a major role in chronic disease is important, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle. The challenge is objectively measuring the health of the mitochondria. Here are some tips to help you evaluate your patients for mitochondrial dysfunction.

How to Test for Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Most clinicians aren’t doing biopsies to count and assess mitochondria directly; the more practical option involves labs showing dysfunction or interruption in the ATP production process, like organic acid panels or levels of oxidative damage, such as oxidative stress tests, lipid peroxides, glutathione levels, or 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). If you run basic lab markers, then you may notice indicators of oxidative stress without realizing they also point to mitochondrial burden. For example, hemoglobin A1C or oxidized LDL are labs commonly run for diagnoses like diabetes or dyslipidemia, but these elevated markers are indicators of increased reactive oxygen species (ROS). Because the Krebs cycle supplies the body with its primary energy needs, when issues arise, patients often present with symptoms like fatigue, pain and accelerated aging.

Organic Acid Panels

Organic acid panels are like an emissions test for your vehicle. Just like an emissions test indicates how efficiently your engine burns fuel, organic acid panels indicate how efficiently mitochondria produce ATP. Certain nutrients are necessary for the chemical reactions of metabolism, and when they are deficient, specific markers in the urine indicate where the deficiency is occurring. If abnormalities are found on organic acid panels, the production of ATP is most likely incomplete, indicating the need for mitochondrial support. For full lab examples and interpretation, see the Immune Foundation In-Practice Guide.

Oxidative Stress Panels

Oxidative stress panels evaluate antioxidant reserve availability, protective enzyme functionality, and the presence or absence of tissue damage. Many clinicians recommend glutathione supplementation to support antioxidant capacity, but a full panel may also indicate the need to support precursors for glutathione production or cofactors needed for recycling capabilities of a redox reaction. Abnormalities on oxidative stress panels are a strong indicator of reduced antioxidant capacity and need for mitochondrial support. For full lab examples and interpretation, see the Immune Foundations In-Practice Guide.

8-Hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine

8-OHdG is a biomarker measured to assess the effect of endogenous oxidative damage to DNA. It can be tested singularly or is included on some hormone panels and nutrient deficiency tests. This marker is often used to estimate cancer and chronic disease risk because it indicates antioxidant systems have failed and damage to lipids, proteins and DNA has occurred. In nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, 8-OHdG is elevated due to free radical-induced lesions. In patients with elevated 8-OHdG, it is imperative to not only find the source of damage but to also provide support for antioxidant capacity.

Oxidized LDL

Strongly atherogenic, oxidized LDL particles (oxLDL) are indicators of damaged fats. They are readily accumulated by macrophages/foam cells, and elevation in this marker indicates excessive oxidative damage. This establishes the necessity for increased antioxidant capacity and mitochondrial support in these patients. For more information on dyslipidemia testing, see the CM Vitals In-Practice Guide.

Subjective Indicators of Mitochondrial Dysfunction

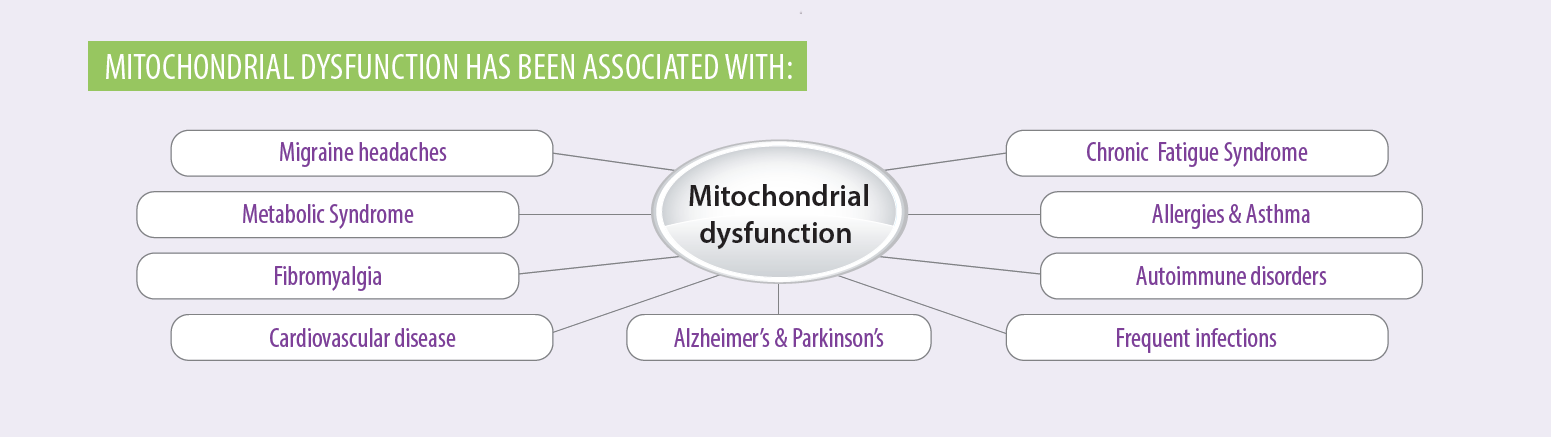

Due to the nature of the practice, testing is not used extensively by some clinicians. In addition, there are some less objective strategies for identifying the need for mitochondrial support. When assessing patient history and chief complaints, it is common for patients to complain of extreme fatigue, pain or weakness. Often, they arrive with a chronic disease diagnosis like autoimmunity, metabolic syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, or fibromyalgia. These diagnoses indicate the need for mitochondrial support.

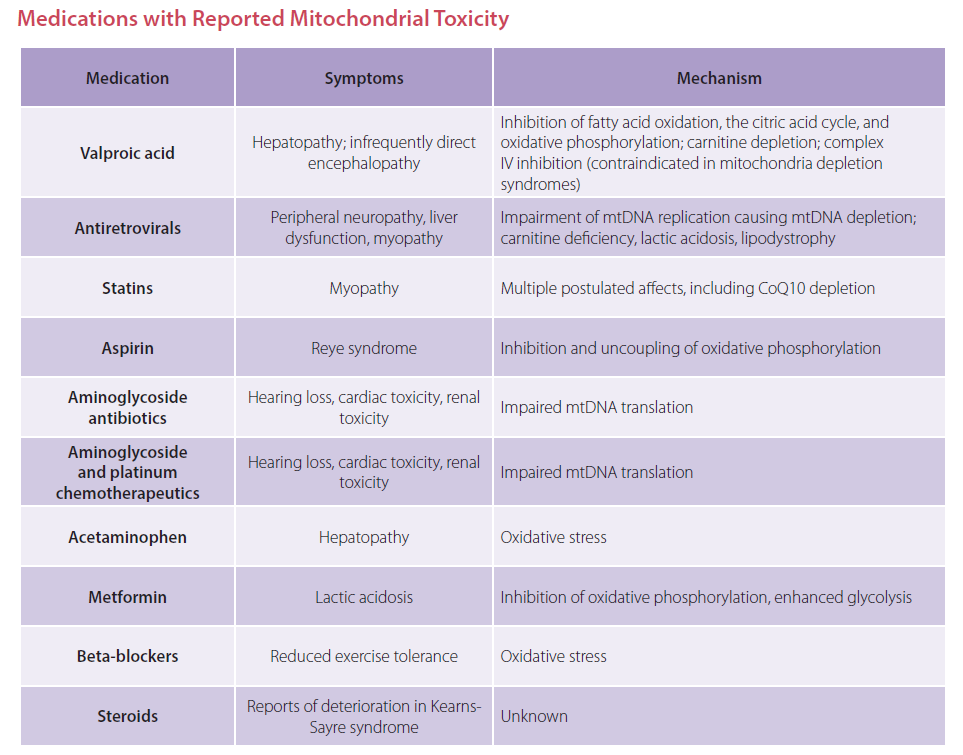

In the medication portion of the intake paperwork, it may be apparent that patients are taking medications such as statins, metformin or steroids, which have known mitochondrial toxicity. If they indicate the use of these medications, consider recommending mitochondrial support nutrients. Check out this illustrative patient education tool on mitochondrial health, diet and lifestyle.

For more information on medications and mitochondrial dysfunction, see the Immune Foundations In-Practice Guide.

Nutrient Support for Mitochondrial Health

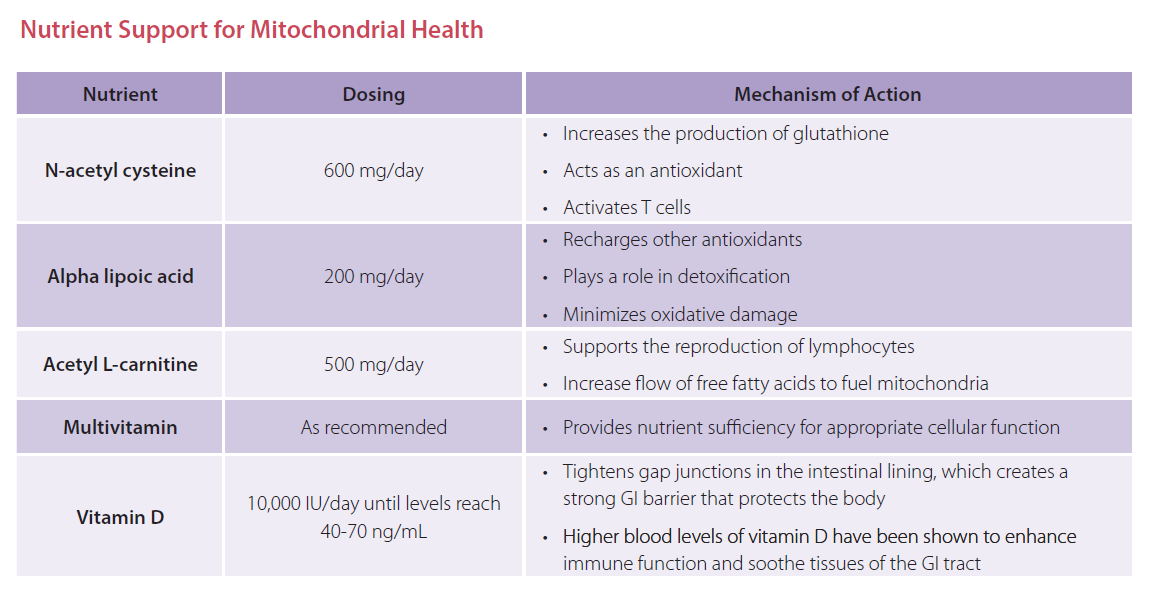

If your patients are taking these medications, you might be asking what nutrients have powerful impact on mitochondria and their ATP production. There are specific nutrients and levels shown to drive ATP production while also quenching the ROS produced as a byproduct. See the nutrient chart below for nutrient considerations. For more detailed information, reference the Immune Foundations In-Practice Guide.

The Bottom Line

Mitochondrial decline has been identified in chronic disease and aging for many years. However, making the connection clinically has been a somewhat slower adoption since the test indicators are not standard labs. If you are treating chronic disease patients, you should consider assessing the need for mitochondrial support and implementing protocols. This often overlooked piece just might solve the puzzle of autoimmunity, detoxification capacity and cardiovascular disease.

Angela Lucterhand, DC received her doctorate in chiropractic from Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa. While there, she was a graduate teaching assistant for courses including Anatomy and Physiology, Histology, the Central Nervous System, and Spinal Anatomy. She received her Bachelor of Arts at Indiana University.

Her interest in basic health care led her to become a Health Education Specialist with the Peace Corps, where she served in Mali, West Africa. Dr. Lucterhand loves teaching and was an adjunct professor for Anatomy and Physiology at Ivy Tech. Her passion in practice is addressing the root causes of disease and emphasizing the impact of lifestyle medicine.