As a health care provider, you regularly see patients managing varying levels of stress. This stress comes from external and internal sources, meaning emotional stress, as well as infections or other physiological dysfunction.1 The number-one

challenge I see with patients and a primary internal stressor is blood sugar regulation.

Dysregulation of blood sugar can negatively impact the body and create internal stress by forcing the body to constantly work on homeostatic balance

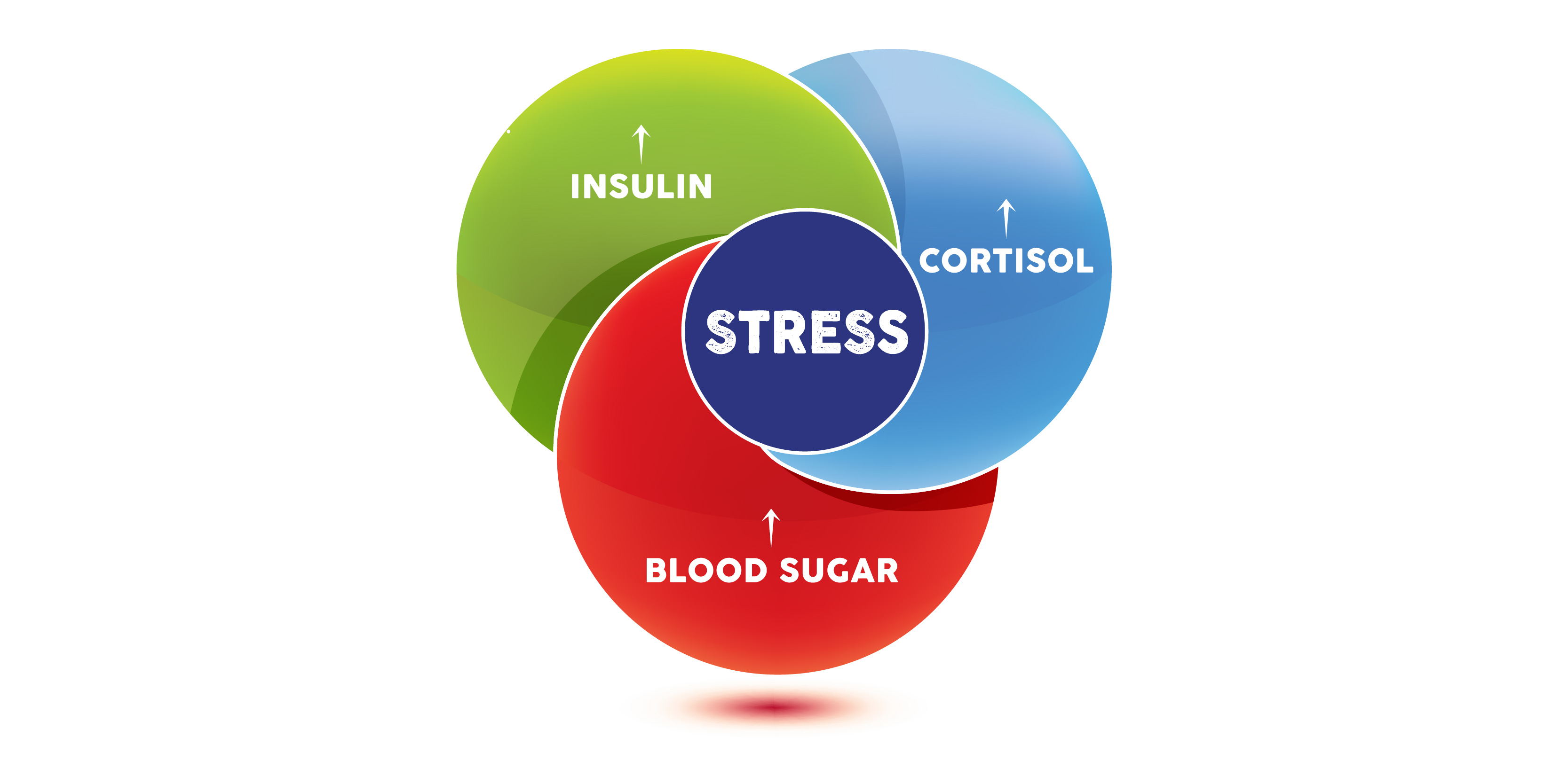

outside of normal physiologic ranges. Conversely, other stressors impacting the body’s regulatory mechanisms through the stress response system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, can lead to blood sugar fluctuation.2,3 Let’s take a closer look at this potential vicious cycle and learn why it’s so important to control blood sugar and the stress response.

Symptoms of Blood Sugar Dysregulation and Evaluation

Obvious symptoms of blood sugar dysregulation are fatigue, shakiness, irritability and even an irregular or fast heartbeat. Where is the first place to begin to evaluate if you suspect blood sugar is the cause of these symptoms? A questionnaire can be

helpful with your intake paperwork, such as the 4 Key Stressor Questionnaire from the SOS Stress Recovery Program.

This questionnaire includes a section that will indicate whether blood sugar is the cause of your patients' mood swings and brain fog. The next step is to order foundational blood work including a fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c and

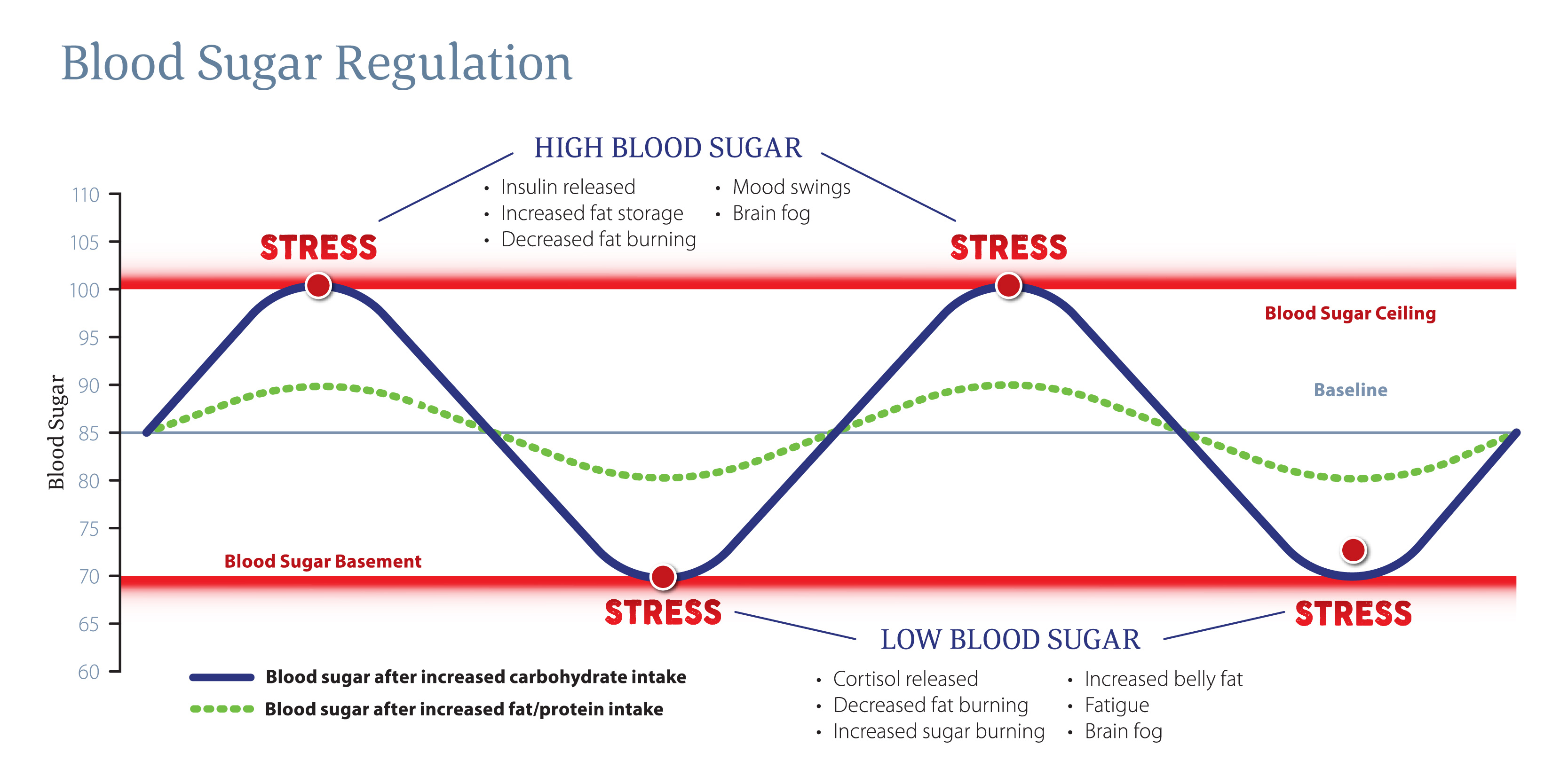

maybe even a fasting blood insulin. If your patients reveal they are eating high glycemic meals or skipping meals regularly, then we can anticipate their blood glucose will spike and crash outside the normal range of 70 to 100 mg/dL.

How Blood Sugar Causes Stress on the Body

As we discussed earlier, our body recognizes blood sugar out of a normal range as a stressful event. The response to high blood sugar is to release insulin, the hormone that promotes the absorption of glucose from the blood so it can be used as energy

by the body.4 This happens naturally when we eat a meal. High blood sugar stimulates fat storage, decreases fat burning and can cause mood swings and brain fog. If for whatever reason we go out of that range too often, the body may start

to overshoot insulin release and instead of lowering blood sugar appropriately, we may end up with blood sugar at the basement level, which as you know, is recognized as a stressor to the body. Low blood sugar triggers release of cortisol, which is

widely known as the stress hormone that provides the body with glucose by tapping into stores of glycogen through a process called gluconeogenesis.

The concept is to give the body the necessary energy it needs to flee from danger. Danger

to the human body used to be running away from predators, but in today’s society, danger is often perceived stressors such as work deadlines and overscheduling.

Low blood sugar can be the end result of consuming high sugar meals regularly and creating an overcompensating response. It can also be due to skipping meals and not providing the body enough sugar to keep the body energized for daily activity. The symptoms of low blood sugar greatly overlap those of high blood sugar; decreased fat burning, increased belly fat, fatigue and brain fog. They can also be misconstrued as other hormone imbalances such as cortisol, thyroid and sex hormones and even neurotransmitter levels.

Stress Causes Blood Sugar Dysregulation

Blood sugar regulation is not just about food choices and meal timing. Stress activates a response system to ensure the body has enough energy, and therefore sugar, to be ready for action. Remember, stress comes in many forms: mental and emotional stress,

glycemic control, inflammation and sleep cycle regulation.5,6

The HPA axis does not discriminate by the type of stressor to determine its activation and outcome; it just knows there is stress and it responds. Cortisol is known

as the stress hormone and is released when stress activates the HPA axis. As we now know, cortisol increases blood sugar. If we already have high blood sugar from our meal, our body receives a double-whammy and we end up needing more insulin to manage

it all. As you see, this can lead to that unfortunate vicious cycle we mentioned in the beginning. The more stress we have, the greater chance our blood sugar levels will fluctuate more often and lead to dysregulation over time.

The Bottom Line

In practice, one of the preeminent ways to decrease stress on the body is to maintain control of blood sugar. With that said, depending on the patient, it could be a difficult factor to modify. When we ask someone to tell us what a typical day of eating looks like, they may be hesitant to admit to the third cup of coffee or the donut for lunch. Have you ever asked for a three-day food diary and been given the "dog ate my homework” response? I know I have! Beyond giving them a list of foods that are acceptable to eat and some healthy snack ideas, what can we do? Whether it is overeating, undereating or not eating the right foods, we should develop a solid method of recognizing this in our patients and have rationale to send them for the appropriate testing.

My tactic is to understand if it really is their diet and eating habits that are causing their blood sugar issues or if there is a high burden of daily stress. If stress is highlighted as an issue based on their questionnaire and your conversations with them, I recommend testing their HPA axis through a salivary cortisol test. This will give you a better understanding of their situation. With the test results in front of them, you can ask questions about what they are doing during the time of day where we see peaks and valleys in their cortisol levels, as these directly correlate with their blood sugar highs and lows. We can ask about the quality and quantity of their food, stress and energy levels. We know blood sugar is a major driver of stress and creates a stress cycle. With this knowledge, we are better equipped to provide education and direction for patients to help keep their blood sugar and stress levels in check.

Stacey Smith, DC earned her doctorate in chiropractic from the National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) in Lombard, Illinois in 2004.?She obtained two bachelor of science degrees, biochemistry from Michigan State University and human biology from NUHS.?She worked alongside her chiropractic parents and brother in a family practice in Michigan for 16 years and focused on lifestyle and physical medicine.?She continues her education of integrative evaluation and treatment practices through functional medicine coursework and utilizes her research and clinical background as the SOS Stress Recovery Program Brand Manager.

References

- Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., Stepanovic, J. Stress and personality. Psychiatriki. Oct-Dec 2011;22(4)290-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22271841/

- Mishra, A., Podder, V., Modgil, S., Khosla, R., Anand, A., Nagarathna, R., Malhotra, R., Nagendra, HR. Higher Perceived Stress and Poor Glycemic Changes in Prediabetics and Diabetics Among Indian Population. J Med Life. 2020 Apr-Jun;13(2):132-137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32742503/

- Goetsch, VL., Weibe, DJ., Veltum, LG., Van Dorsten, B. Stress and blood glucose in type II diabetes mellitus.Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(6):531-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2076091/

- Guilliams, T. The Role of Stress and the HPA Axis in Chronic Disease Management. The Standard Road Map Series, Second Edition. 2020. ISBN: 978-0-9856158-7-1.

- The 4 Key Stressors: Prioritizing Lifestyle Intervention Strategies for Stress Recovery. https://ompi.wistia.com/medias/l5jj67e8b2

- The 4 Key Stressors and Nutritional Support Protocols for Rebuilding Stress Resiliency https://www.lifestylematrix.com/blog/the-4-key-stressors-and-nutritional-support-protocols-for-rebuilding-stress-resiliency/